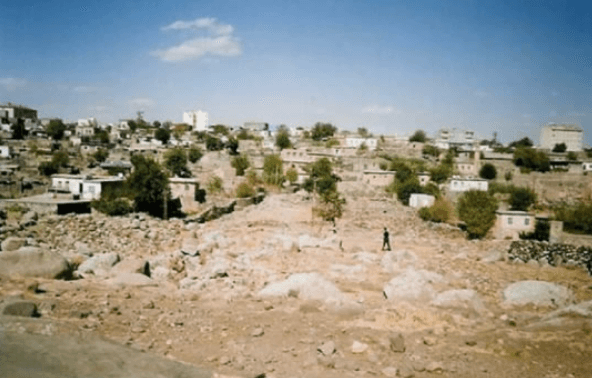

Azakh, historically referred to as Beth Zabday or by its modern name Idil, stood as a significant settlement west of Jazira. At the onset of the 20th century, the village sustained a population of approximately 1,000 inhabitants. These residents were primarily Arabic-speaking Christians belonging to the Syriac-Aramean Orthodox and Syriac-Aramean Catholic churches.

Omer Naji Bey, a former CUP Inspector General known for his intelligence work and oratory skills, found himself in a humiliating position outside this village. Halil Bey, an old associate from his days in espionage, had maneuvered him into leading a siege against this small settlement defended by only a few hundred men. Despite commanding thousands of cavalry, foot soldiers, and local militia equipped with modern weaponry and cannons, Naji failed to break the resistance. Even a direct telegram from Enver Pasha demanding that Azakh be “suppressed immediately with the utmost severity” yielded no results. The defenders eventually launched a surprise night attack through tunnels, routing the sleeping army and capturing a significant cache of weapons. With his artillery disabled and his forces in disarray, Naji’s expedition collapsed.

Defeat was particularly bitter for Naji, whose primary mission lay in Iran. There, he intended to collaborate with German allies to incite a Kurdish uprising. Instead, he wasted valuable time and resources bombarding a Syriac-Aramean village. He was also baffled by the local insistence on labeling the rebels as Armenians, given that Syriac-Arameans were theoretically exempt from the worst of the government's atrocities.

Command of the siege was eventually transferred after this failure. Naji had previously requested to abandon the operation but was denied, as the state viewed crushing the revolt as a matter of prestige. His initial appointment had been part of a scheme by Halil to implicate the German officers accompanying the detachment in the anti-Christian massacres. However, the Germans refused to participate, escalating the local failure into an international incident. This marked a tragic end for the former political boss and guerilla leader, who felt exiled from power. He died shortly thereafter under unclear circumstances.

THE “MIDYAT REBELLION”

Armed resistance began to organize among Syriac-Arameans, Chaldeans, and Armenian refugees in response to the slaughter occurring throughout the southeastern Diyarbakir province. Ottoman authorities, having worked diligently to pacify the region, found this defiance deeply embarrassing. El-Ghusein wrote:

“The Syriac-Arameans in the province of Midiat were brave men, braver than all the other tribes in these regions. When they heard what had fallen upon their brethren at Diarbekir and the vicinity they assembled, fortified themselves in three villages near Midiat, and made a heroic resistance, showing courage beyond description. The Government sent against them two companies of regulars, besides a company of gendarmes, which had been dispatched thither previously; the Kurdish tribes assembled against them, but without result, and thus they protected their lives, honour and possessions from the tyranny of this oppressive Government. An imperial Iradeh [decree] was issued, granting them pardon, but they placed no reliance on it and did not surrender, for past experience had shown them that this is the most false Government on the face of the earth, taking back to-day what it gave yesterday, and punishing to-day with most cruel penalties him whom it had previously pardoned.”

Consul Walther Holstein in Mosul reported on July 28 that a revolt involving “both of Chaldeans and Syriac-Arameans” had severed the telegraph line to Diyarbakir. He noted: “This uproar is a direct consequence of the extreme actions of the vali of Diyarbekir against Christians in general. They are trying to save their skins.” Reports also indicated that the Yezidis of the Sinjar Mountains had joined the unrest. The German ambassador in Istanbul messaged Reichskanzler Bethmann Hollweg regarding the Tur Abdin situation:

“At the beginning of this month, the vali of Diyarbekir, Reshid Bey, started a systematic extermination of the Christian population of his jurisdiction, without difference to race or confession. Of these particularly the Catholic Armenians of Mardin and Tel-Armen and the Chaldean Christians and non-Uniate Syriac-Arameans [that is Syriac-Aramean Orthodox and Protestants] in the districts of Midyat, Jazira, and Nisibin have been victim. According to information obtained by the consulate in Mosul, the Christian population between Mardin and Midyat has risen up against the government and destroyed the telegraph lines.”

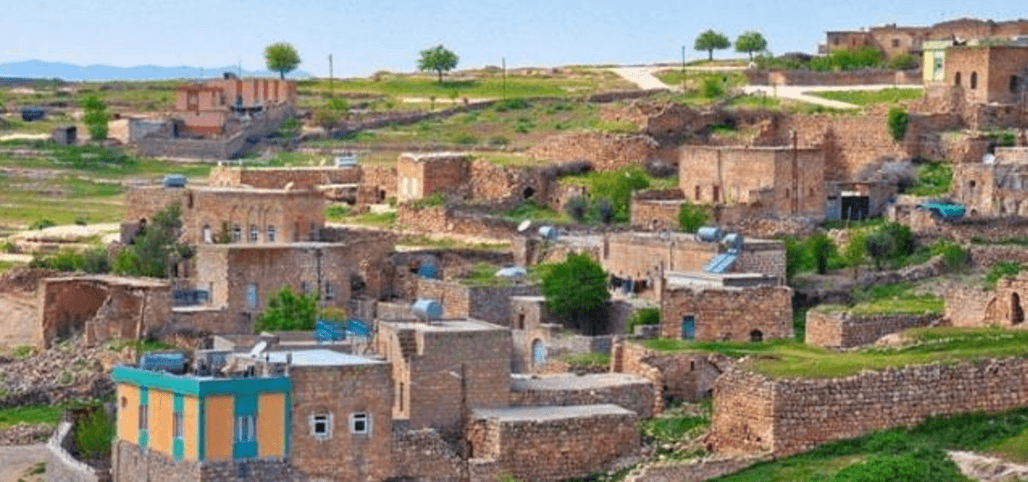

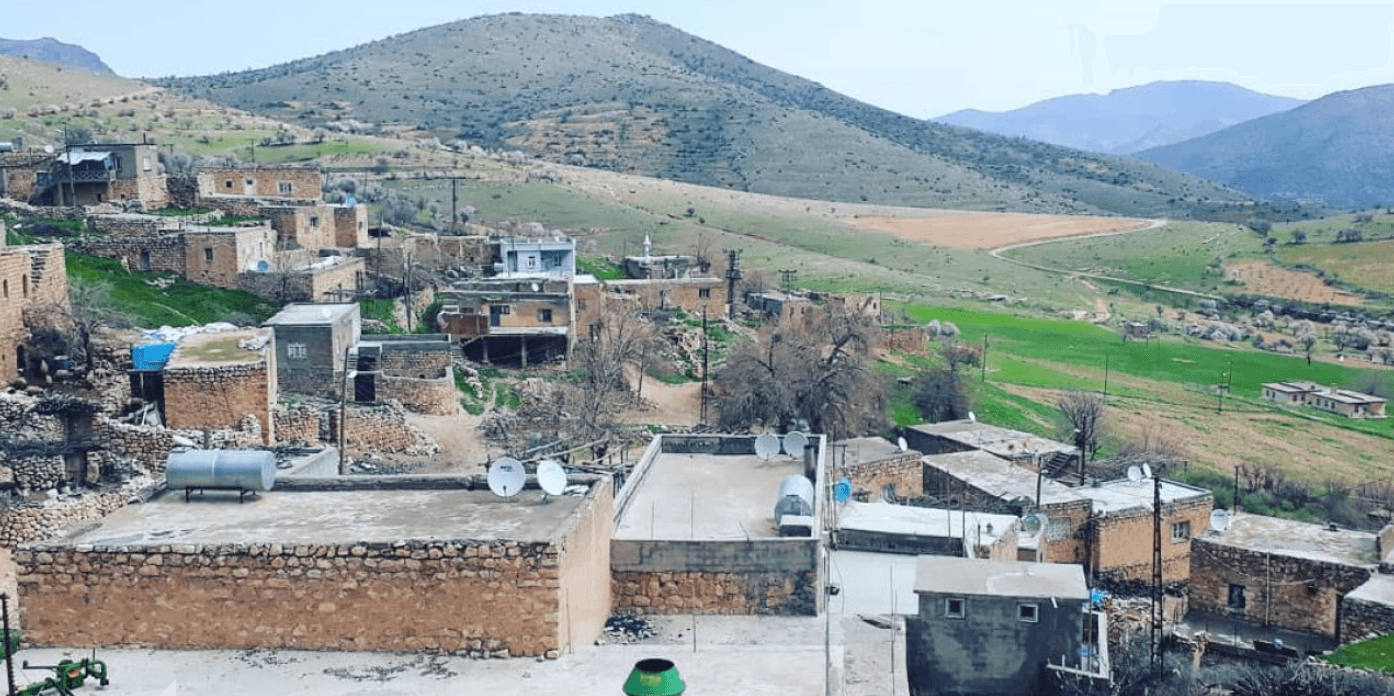

Key centers of resistance included Azakh (Idil), Iwardo (Gülgöze), Dayro da Slibo, Hah, Basibrin, and Beth-Debe. Monastic complexes such as Mor Malke, Zafaran, and Mor Gabriel also served as potential fortresses. While these sites successfully repelled initial attacks by undisciplined Kurdish tribes, the defenders remained trapped inside, unable to tend to their flocks or fields. Survival necessitated night raids on Kurdish villages for food, which escalated the conflict and drew the full attention of the Ottoman army. Orders to pacify the region were initially sent to the Fourth Army, but distance prevented a timely response.

Abundant documentation allows for a detailed reconstruction of events in Azakh, home to roughly one thousand Syriac-Aramean Orthodox and Catholics. Prior to the siege, the population swelled with refugees from neighboring villages and escapees from Armenian deportation convoys. Hinno’s oral history recounts that village headmen gathered under the leadership of Syriac-Aramean Bishop Mor Behnam Aqrawi to select a commander. A lottery chose Yesua Hanna Gawriye, who then organized fortifications, tunnel construction, and the manufacture of ammunition. They swore to a traditional motto: “We all have to die sometime, do not die in shame and humiliation.”

Anticipation of violence grew well before Feyzi Bey, a National Assembly deputy, arrived in Jazira on April 15, 1915, to coordinate local Kurdish tribes. Upon his departure, these tribes besieged Garessa and Kuvakh, forcing the residents to flee to Azakh. Historically known as a place of asylum, Azakh possessed strong defensive walls and was administered by a government official, the Bucak Müdürü, who commanded a local gendarmerie detachment.

Diaries kept by Gabriyel Qas Tuma Hendo, a Syriac-Aramean Catholic priest, chronicle the encroaching danger. In mid-May, Jazira's military leadership inspected the village, demanding the surrender of tall buildings for "defense." On May 25, the chief of the Rama tribe scouted the fortifications. While bribes initially saved Azakh from the tribes attacking Babeqqa, the violence shifted to Esfes on June 6. There, villagers defended themselves until Al-Khamsin militiamen betrayed them after being allowed inside. A bribe paid by priest ‘Abdallahad Jebbo eventually allowed the Esfes residents to escape to Azakh while their homes were looted and burned.

Government officials repeatedly attempted to weaken the defense by luring refugees back to their homes. On June 11, an officer promised safety to those from Garessa and Kuvakh, but they refused to leave. This officer also met with Hasse Barakat, head of the Botikan clan. Barakat declined to attack Azakh, citing a blood oath of peace, though he allowed his son to lead the tribe in his stead. As Kurdish forces gathered in Rizo from Midyat, Jazira, and Nisibin, Babeqqa came under siege again, and its residents fled to Azakh.

Planning for the assault began in earnest with a meeting of Kurdish chiefs on July 1. Gabriyel Khaddo, a leading Syriac-Aramean in Jazira who believed collaboration would save his community, arrived on July 5. He demanded the surrender of all Catholics and Protestants, promising safety for the others. The villagers rejected this, asserting a unified Syriac-Aramean identity, despite the presence of hidden Armenian refugees. On July 6, Turkish soldiers attempted to billet inside the village but were forced to camp outside. By July 9, Al-Khamsin militia under Ahmed Nazo had joined the gathering forces.

Religious overtones quickly defined the conflict. On July 10, government troops camped nearby went silent while Kurdish tribes mobilized. Inside Azakh, defense committees formed, and priests delivered sermons. Preparations included building sniper posts and digging tunnels. A suicide squad known as the fedais of Jesus formed under Andrawos Hanna Eliya and Ya’qub Hanna Gabre. The attack was paused for Ramadan but resumed immediately afterward.

A signal fire on ‘Alam hill on August 14 marked the beginning of hostilities. Officials from Jazira arrived two days later with modern weapons for the tribes. By August 17, the Miran, Hamidi, and other clans surrounded the village. A massive frontal assault occurred on the 18th, but the next morning revealed heavy attacker casualties. On August 26, the fedai launched a night raid that destroyed Kurdish positions. By September 9, the tribes retreated, having suffered significant losses compared to the 50 defenders killed.

Frustrated Kurdish tribes turned their aggression toward Jazira, initiating waves of massacres organized by local notables. Authorities then refocused on Tur Abdin. Hinno notes that the ringleaders in Jazira:

“sent a report to the government and accused the Syriac-Arameans of being Armenians, rebels, and guilty of destroying the villages in the area. When the report came to the authorities, they sent commander Omer Naji with 8,000 fully equipped soldiers to Azakh, and in addition these soldiers were joined by Kurdish rebels from the clans in Nisibin, Sirnak, and Tel-Afar.”

NAJI AND SCHEUBNER-RICHTER

Historical records confirm Omer Naji Bey’s leadership. A CUP insider and "Teskilat-i Mahsusa" member, Naji was a powerful orator and political operative. German observer Paul Leverkuehn called him one of the most “remarkable figures of the Turkish political world” who “enjoyed the unconditional trust of all the Young Turk politicians and had the authority, if one can say so, of a master prophet.” He partnered with Max von Scheubner-Richter, a German officer and former vice-consul, to lead an expedition into Iran to incite anti-Russian uprisings.

Near Sa’irt, the expedition encountered Halil Bey, Enver Pasha's uncle, who was marching south. Halil, fresh from defeats in Persia and massacres in Sa’irt, traveled with a caravan that Leverkuehn described as belonging to an “ambitious political and military dilettante.” German officers noted a bathtub among his luggage, speculated to be for the women he had abducted.

Scheubner-Richter held military command, while Naji acted as political commissar. Regular army officers viewed them as adventurers. Naji’s appointment over the experienced Halil was unusual, likely an attempt to involve German officers in anti-Christian operations. Scheubner-Richter, despite holding racist views, opposed the annihilation of Armenians and filed protests, creating friction with Turkish allies.

While passing near Tur Abdin, Naji received orders to coordinate operations against the Christians. Resistance in Azakh, Iwardo, and Basibrin tied down Ottoman troops, drawing attention from General von der Goltz and Enver Pasha. Eventually, ceasefires were negotiated in Azakh and Iwardo.

SYRIACS OR ARMENIANS?

On October 29, 1915, Naji reported that Syriac-Aramean Christians had revolted in Diyarbakir, Jazira, and Midyat and were “cruelly massacring” Muslims. He requested permission to “chastise” the rebels. His telegram stated:

“I am in Jazira with a detachment of troops bound for Persia. In the districts of Diyarbekir, Midyat, and Jazira, which are situated one hour distant from here, the Syriac-Aramean Christians have revolted and are cruelly massacring the Muslim people in the area. I will go there with my troops to punish the rebels who, it has been reported, have 4,000 arms, though I think this is an exaggeration. My troops consist of 650 cavalry and infantry soldiers. We have two mountain guns. I request that a battalion from the Fifty-first Division, which is due to arrive in Jazira, with a number of mountain artillery, be ordered to join our troops.”

Naji requested reinforcements despite local claims that the rebels were Armenian. He likely knew the truth but feigned ignorance until later claiming he lifted the siege upon "realizing" they were Syriac-Arameans. Before hostilities, he met with village headmen in Arabic. A second meeting on November 7 turned hostile when he demanded disarmament. Naji tried to enlist Scheubner-Richter, but Leverkuehn recorded the German's refusal:

“In the mountains west of the Tigris, fleeing Armenians had fortified themselves in some villages inhabited by Syriac-Aramean Christians that refused to obey the Turkish authorities to deliver requisitions of foodstuff and military recruits. The vali of Diyarbekir demanded of Constantinople that it order Naji’s and Scheubner’s troops to conquer these villages. Omer Naji telegraphed Scheubner asking if he would place his detachment and the Germans under his command, as desired. Scheubner, however, was placed in a difficult situation by this demand. He was in no way convinced by the Turkish description [of the background]. Rather, he had the view that this was not a real rebellion but concerned a not unjustified defense by people who feared meeting the same fate as most Armenians. If the Germans participated now, the Turks would not shrink from intimating that it was they [the Germans] who had led the [atrocities] against the Christian Turkish subjects. ... Under these circumstances, Scheubner therefore placed all of the Turkish troops and Kurdish cavalry under Omer Naji’s command, but ordered Leverkuehn, Thiel, and Schlimme [the German officers] to come immediately to Mosul.”

Scheubner allowed Turkish troops to participate but kept Germans out, labeling it an “inner Turkish” affair. General von der Goltz supported this, while Ottoman officials expressed disappointment, confirming Scheubner's suspicion that this was a ploy to implicate Germany in the “Armenian affair”.

Armenian fighters played a negligible role, as they are absent from Hinno’s oral history. Hendo's diary mentions only about eighty Armenian refugees hiding in Azakh. Officials exaggerated this presence to justify the attacks. While Naji used the term Süryani (Syriac-Aramean), others used "Armenian" or "rebels." General Halil Bey telegraphed the Supreme Military Command:

“Upon my arrival in Jazira I found that, nearly 50 kilometers west of Jazira, in the village of Hazar [Azakh] from various neighborhoods and villages in the vicinity, up to 1,000 armed Armenians gathered lately and started an assault destroying Muslim villages nearby and massacred their inhabitants and cut the telegraph line between Jazira and Diyarbekir. As there is no force in this area to punish them, this assault will continue. Naji Bey from the Third Army with a force under his command, [who] is on his way to Iran, is currently in Jazira. I do not think he has pressing duties and [will wait] until the arrival of a formal order. I submit that if they are not to be relied on, I request it would be appropriate to order the Fifty-Second Division to punish them.”

Temporary vali Bedri Bey reported on the casualties using the generic "rebels":

“In the course of the punishment of the rebels in the Midyat region, they were first of all asked to give up their arms. [One] could not be certain about the accessibility of the terrain in such places as Basabriye [Basibrin] and Azakh where the rebels are in great numbers. Two or three villages that were isolated [did already] surrender and although they were forced to lay down their arms, [did so] with half-hearted confidence; they handed over to the government ineffective weapons and concealed the rest. Rebels in other places dared to respond to the proposal by firing guns and by means of patrolling [raiding?] Muslim [areas] and attacking and massacring the inhabitants. They fortified themselves in the village of Azakh and fortified the village with walls and trenches. Assigned to the punishment of about 10,000 rebels, Omer Naji Bey, commander of the Iran expedition force, after the blockade of the village with the troops and the military, proposed peace and asked them to surrender their weapons. They had the insolence to respond to this proposition by causing 38 wounded, including two officers, and three shahids [martyrs] in the detachment.”

Real defender numbers were lower, and Turkish casualties higher, than reported.

Troop movements required high-level authorization. Special "Teskilat-i Mahsusa" units and volunteers under Circassian Ethem (Cerkez Ethem) were deployed. A communiqué on November 7 suggested: “I submit that in order to assist Omer Naji Bey, 500 fighters that have been organized under militia commander Edhem Bey could be moving within two days.” A handwritten note added: “It will be discussed with Naz [Minister] Pasha.” Talaat Pasha confirmed the order the next day:

“In a telegram dated November 7, 1915, that has arrived from the province of Mosul... it was communicated that in order to assist Omer Naji Bey, 500 fighters under militia commander Edhem Bey have been organized and they would be moving within two days. In this matter command belongs to Him to whom all commanding belongs.”

Ethem was known for brutality and his role in Reshid Bey’s private army.

Enver Pasha issued orders to the Third Army commander in Erzerum:

“Omer Naji Bey reported that the Syriac-Arameans between Midyat and Jazira have united with the Armenians and cut the telegraph lines and attacked the Muslim people. To suppress them, Omer Naji Bey’s detachment, plus a battalion of infantry and two mountain artilleries, have departed from Urfa and are moving toward Jazira. ... The rebels and the districts they attacked [are located] within the jurisdiction of the Third Army, and because of this, the movement of the detachment [should be coordinated by] the headquarters of the Third Army. If the uprising of the rebels is warded off [and they] give up arms ... if they consent to be [resettled] in a locality selected by the government. Even if it is not true about their attack and massacres of Muslim people.”

Enver identified the villagers as Syriac-Arameans and doubted the atrocity claims. Naji also had doubts. When his troops arrived, Syriac-Aramean notables brought food and, according to Hinno: “The Syriac-Arameans explained to him that the accusations against them were false and groundless, and that they were neither enemies of the state nor traitors and that they were prepared to follow his orders with respect.” Hendo’s diary notes that headmen denied the presence of Armenians. Naji seemed convinced until Kurds provided contrary information, leading him to refuse further meetings and plan the attack.

November 7 and 8 marked the first assault. A Turkish officer, urging his men to “show no mercy,” was shot in the forehead. Artillery failed to breach the walls, and subsequent trench warfare tactics also failed to break the defense.

Berlin was fully informed. Ambassador Neurath wrote to Bethmann Hollweg on November 12:

“As a result of his mission to the east Anatolian theater of war, Field Marshal von der Goltz asked me to let him see the copies of the records of the embassy concerning the Armenian question and at the same time to orient him on our standpoint on this question. I have sent him the attached notes. The request of the Field Marshal was caused by the Expedition against a number of Christians of Syriac-Aramean confession that has been planned for a long time. They are allied with Armenians and have fortified themselves in difficult terrain between Mardin and Midyat in order to get away from the massacres of Christians that the vali of Diyarbekir has organized. Since the original detachment designated for this mission from the Fourth Army is too distant, he asked the Field Marshal for a detachment of the Third Army to be ordered to restore order there. The consul in Mosul, Holstein, for his part pointed out that this is not a real uproar, and with the understanding of the vali in Mosul wishes that negotiations take place with the besieged and that among other personalities Herr von Scheubner-Richter, whose troops are anyway participating in the mission, shall participate and take part in the negotiations. The Field Marshal rightly not wishing German officers to get involved in this affair, has given the order that Herr von Scheubner’s troops will not be included in the expedition in question.”

Ottoman forces grew to include Halil’s divisions, mountain howitzers, and Ethem's mujaheddin. Syriac-Aramean sources estimate 8,000 soldiers. Reinforcements even arrived from the Fourth Army in Syria.

NAJI’S DEFEAT

A turning point came on the night of November 13-14. The fedais emerged from tunnels to ambush sleeping Turkish soldiers. Chaos ensued, allowing the Syriac-Arameans to kill hundreds and capture modern rifles to replace their primitive flintlocks. This shock led Naji to plead for more help.

Naji proved better at ideology than strategy. Heavy losses and the inability to conquer a village embarrassed the army and delayed the Iran mission. Truce discussions began, though Naji needed to save face. The Syriac-Arameans refused to surrender arms, so fighting continued.

General Kamil Pasha argued that the rebellion was spreading to the Yezidis in Sinjar, necessitating a battalion reinforcement. He telegraphed:

“The rebels in Midyat and Jazira, not only did they not respond to the proposal of Omer Naji Bey, the commander of the detachment of troops set for the village of Azakh, to give up their arms, but they also answered, by shooting, a previous proposal to relinquish their arms, the aforementioned rebels responded by attacking Muslims and massacring Muslim people, and to a third proposal for peace [illegible] that it was not considered acceptable was understood from the correspondence with the Province of Diyarbekir. In the Mosul province the Armenians who took refuge in the Sinjar Mountains united with the local Yezidis and communicated with the Midyat rebels and [urged them] to persevere with their rebellion and [illegible] for encouraging the rebels in Sinjar [we request] an order to do what is necessary to punish and repress the rebellion.”

Negotiations opened on November 16. After Naji offered hostages to ensure safety, village headmen met him. Naji reportedly said:

“You have killed many of my soldiers. But it is only now that I know for absolutely sure that you are not Armenians but Syriac-Arameans. Therefore, I will raise the siege of Azakh and withdraw my force. I propose a truce from now on.”

Azakh’s leaders replied:

“Commander Bey! We have only defended ourselves and that is why we shot. If you really stop shooting and raise the siege, we will not shoot back.”

Naji requested the return of captured weapons, which the villagers denied having. Naji then withdrew his troops on November 21.

ENVER INTERVENES

Enver Pasha in Constantinople rejected the armistice, ordering the village's destruction on November 17:

“The Commander of the Third Army reports that the rebels who attacked in the Azakh village of Midyat [district] responded with fire against Omer Naji Bey’s detachment to his proposal of handing over their arms. And about 100 kilometers west of the area, in Sinjar, the Yezidis and the Armenians together are currently in a state of rebellion. In response [illegible] the detachment which transferred from the Fourth Army and Omer Naji Beys’s detachment if necessary, [is] to be immediately reinforced in order to suppress [the revolt] in the Midyat area. As yet no additional information has arrived about the circumstances in Sinjar. If required, I request that your high office order its investigation and that I be informed of the outcome.”

He sent explicit orders to the Third Army:

“In accordance with the conditions about which I wrote to you and in the event of lack of consent [of the Azakh defenders] to immediately evacuate and repress. Omer Naji Bey’s detachment is still in the vicinity of the village of Azakh and the battalion of foot soldiers and the mountain artillery unit sent from the Fourth Army is in the Midyat region [illegible] from the Fourth Army and from Mosul another force [from the Sixth Army] which can be spared, if necessary these forces from your area [are] to reinforce the Azakh [operation]. Inform of the outcome of the operation.”

Naji was denied permission to leave for Iran. Enver telegraphed:

“I have transmitted the following telegram to the Third Army Command and informed the Sixth Army. The Midyat rebellion should be suppressed immediately and with utmost severity. Accordingly, Omer Naji Bey’s detachment will remain there under the orders of the army.”

Total destruction remained the goal. Kamil Pasha supported Naji remaining in place, fearing the rebellion would grow. He telegraphed:

“The ciphered telegrams regarding communication for Omer Naji Bey’s detachment to depart for Mosul have arrived. In the telegram dated November 22 from the Province of Diyarbekir it is understood that the associates of the rebels are attracting attention [again] and in Midyat the rebellion is growing day by day [and that] they [the rebels] will not ask for mercy and if this matter is not taken care of, [and] in the case that the detachments are transferred to other places in the said district, there is a probability of important unexpected events happening. The foot soldiers of the Fourth Army on their own and without artillery cannot pacify the rebellion as demonstrated by the failure of Omer Naji Bey’s detachment.”

Desperate, Naji defied orders and agreed to a settlement where villagers kept their arms. Enver demanded an explanation:

“Provide information about the following items:

1. Of what nation [millet] are the rebels in the Midyat area? If there are Armenians among them, where are they from and how many are they?

2. With whom, upon what conditions, and in what way did Omer Naji Bey reconcile?

3. Have these conditions been agreed by the rebels? What is the current situation?

4. If you find this settlement problematic what measures do you propose? To what extent is it possible to carry them out?”

Kamil Pasha replied on November 28:

“1. The great part of the rebels in the Midyat region are Syriac-Arameans who are native to the area. They were joined by a small number of Armenians and Chaldeans who escaped from here and there.

2. Omer Naji Bey and the vali of Diyarbekir have reported that the Syriac-Arameans in the village of Azakh had agreed to the conditions of handing over their arms, repairing the telegraph lines they destroyed, paying their debts to the government, and returning to their villages, and that they have solved the matter peacefully. However, they also stated that the arms the rebels handed over constituted an insignificant amount and that furthermore if their domiciles are to be changed [if they are to be deported] and their weapons are going to be destroyed, the rebels will revolt once again.

3. Upon orders from your high office, Omer Naji Bey’s detachment departed for the Mosul border. The commander of the detachment which remained there [in Azakh] in accordance with the condition stipulated in the second item continues to collect the settlement money from the Syriac-Arameans.

4. The matter has been settled in this way and in that region to stabilize order and make these rebels docile and completely obedient to the government, and come what may, the transportation and removal of the abovementioned people to other places will be necessary. At present, the province of Diyarbekir has been informed that if the enemy approaches, this would cause renewed rebellion and banditry. In the opinion of your humble servant, this state of affairs is not acceptable... However, Omer Naji Bey’s failed operation and the lack of available forces to send in that direction necessitate postponement of the engagement to a more opportune moment; ... the matter of when to complete the destruction of the rebellion is a matter that is left to your discretion.”

Naji abandoned the siege to prioritize his Iran mission and stop the bleeding of his troops. Kamil and Enver viewed this as a temporary setback to be rectified later.

Aggression continued elsewhere. On February 14, 1916, the German Ambassador reported that “the difficulties between the Syriac-Aramean Christians at Mardin and Midyat” were resolved. While Azakh survived, the Mardin sanjak was devastated. A November 7 telegram ordered “deserted” villages to be resettled with “immigrant members of the Division of Public Order Cavalry.”

These events demonstrate that rural depopulation was not merely the result of uncontrolled Kurdish tribes. Regular troops and "Teskilat-i Mahsusa" death squads executed the attacks. The resistance of this small village engaged the highest levels of the Ottoman and German governments, proving the German military was more than a passive observer.

In his 1916 report, Scheubner described an order to:

“attack and punish an Armenian [sic] village. I found out that the presumed “rebellious” people were those who had taken cover to save themselves out of fear of a massacre. ... I pulled myself out of this threatening conflict by saying that I and my German officers and men were needed in Mosul. The command over my Turkish troops was transferred to one of my Turkish officers under the motive that this was an “inner Turkish” affair and that it was not proper for Germans to command the “gendarme-service” that the Turkish troops were expected to do. General Field Marshal von der Goltz approved my position. Even the Turkish side admitted this afterward. The disappointment shown then proved the supposition that the order that I received was an attempt by Halil Bey to involve me and the Germans under my leadership, in a compromising way, in the treatment of the Armenians.”

Officers realized Turks were blaming Germany for the expulsions. Leverkuehn concluded:

“the enormous importance of Scheubner’s denial in the so-called uprising near Jazire stands before my eyes in its full political sharpness. Everything that one afterward heard about it justified the stance that Scheubner then had made. The entire uprising was only a matter of the destruction of a telegraph line, and it was done in self-defense, while the Armenian [sic] villages were still under Kurdish attack, and an appeal for help to the kaymakam met with not the least response. Directly, and before he received Scheubner’s order, Leverkuehn could not separate himself from the troops and became a witness of the gruesomeness that the kaymakam tolerated without intervention, in the destruction of peaceful villages and the abuse of the inhabitants.”